Buy The Book

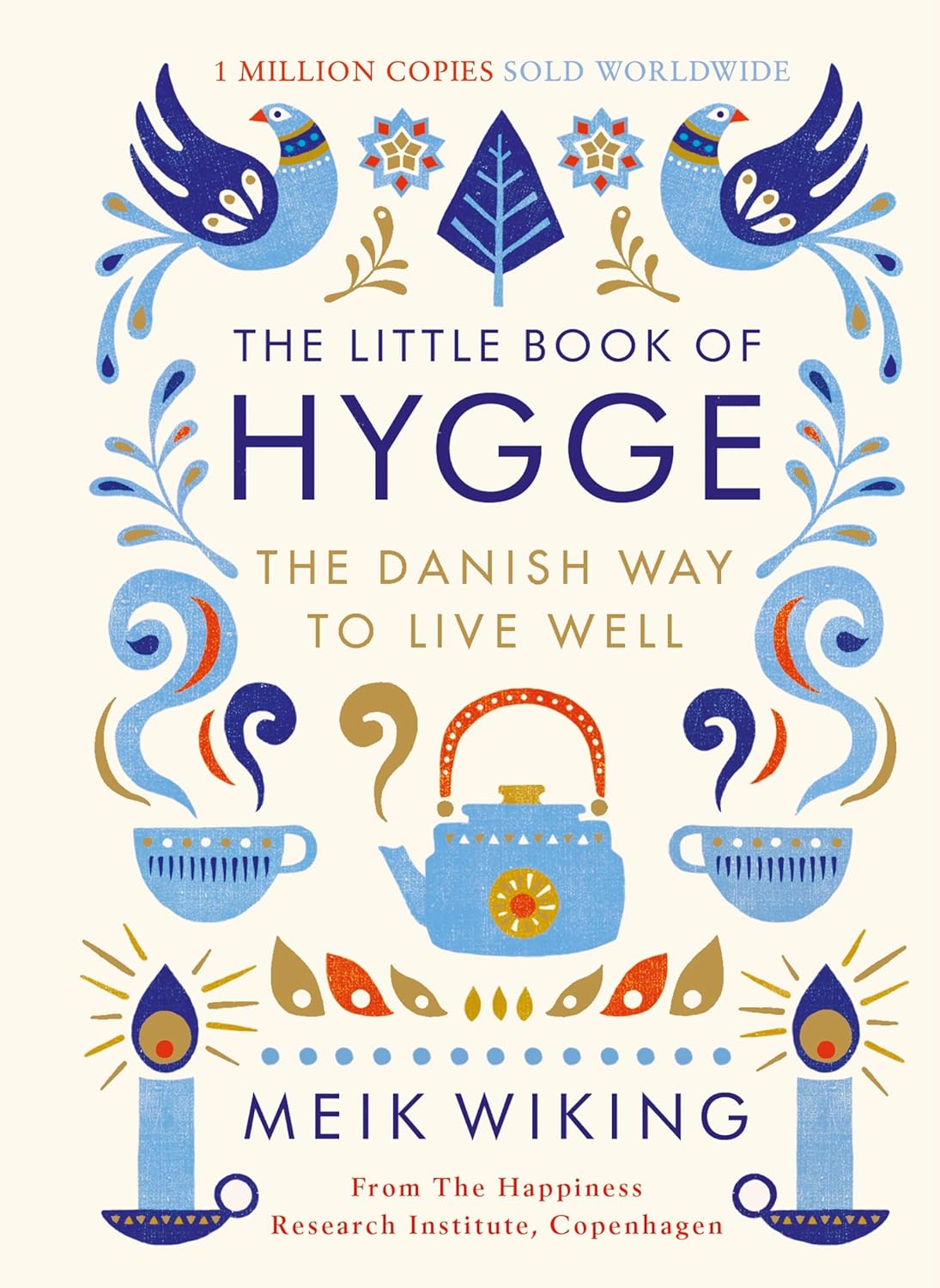

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

About

“Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World” by Cal Newport, the bestselling author of “Deep Work”, addresses the overwhelming impact of technology on our lives. Newport introduces digital minimalism as a philosophy to intentionally use technology, advocating for focusing online time on activities that strongly support one’s values, and happily missing out on everything else. The book is divided into two parts, the first lays the philosophical foundations, and the second provides practices for adopting this lifestyle. Newport introduces the digital declutter, a method for adopting this philosophy, which involves a 30-day break from optional online activities to rediscover offline pursuits. After the break, technologies are reintroduced intentionally based on their value. The book offers strategies for cultivating a sustainable digital minimalist lifestyle, emphasizing solitude, high-quality leisure, and an “attention resistance” to thoughtfully extract value from technology while avoiding compulsive use.

Spark

Learn

Review

✦ Introduction

After my book “Deep Work” was published, I noticed many readers were concerned about technology negatively impacting their personal lives. They felt that the internet, while potentially beneficial, was draining their time and satisfaction. This unsustainable relationship with technology made them feel exhausted, due to apps and websites competing for their attention and manipulating their moods. Compulsive use cultivated behavioral addictions, which made it hard to have the uninterrupted time needed for an intentional life.

My research showed that some addictive properties are accidental, but many are intentional, as compulsive use drives social media business plans. This attraction to screens leads to a loss of control over one’s attention. People downloaded apps for valid reasons, but these services began to undermine their values. Unrestricted online activity negatively impacts psychological well-being. Constant exposure to curated portrayals generates feelings of inadequacy, especially among teenagers, and provides a platform for public exclusion.

Online discussions accelerate emotionally charged extremes; anger and outrage attract more attention than positive thoughts. Heavy internet users unknowingly pay a steep price of negativity for their compulsive connectivity. This collection of concerns motivated me to research those who extract value from technology without losing control, leading to a philosophy of technology use rooted in deep values called “digital minimalism,” answering what tools should be used and how, while confidently ignoring the rest.

PART 1 Foundations

✦ 1. A Lopsided Arms Race

In the spring of 2004, Facebook was just a novelty, a virtual version of our freshman directory, and it didn’t seem like something on which we would spend any real amount of time. The iPhone’s “revolution” was initially much more modest than its eventual impact. It was supposed to be an iPod that made phone calls. The original vision was less grandiose, and the killer app was making calls, not the improved text messaging and mobile internet access that now dominate how we use these devices.

These changes massively and unexpectedly transformed how we live, making moments feel strangely flat if they exist solely in themselves. A college senior setting up a Facebook account in 2004 probably didn’t predict spending around two hours per day on social media, nor would an early iPhone adopter foresee compulsively checking the device eighty-five times a day. We didn’t sign up for this digital world; we stumbled backward into it.

Techno-apologists often highlight the utility of these tools, like a struggling artist finding an audience through social media. However, the source of our unease isn’t in these case studies, but in how these technologies have expanded beyond their initial roles, dictating how we behave and feel, coercing us to use them more than we think is healthy, often at the expense of more valuable activities. It’s not about usefulness, it’s about losing control.

Many of these new tools are not as innocent as they seem. We don’t succumb to screens because we’re lazy, but because billions of dollars have been invested to make this outcome inevitable. We were pushed into it by high-end device companies and attention economy conglomerates who discovered vast fortunes to be made in a culture dominated by gadgets and apps. Checking your “likes” is the new smoking.

These apps are like slot machines, using a whole playbook of techniques to get you using the product for as long as possible. They are programming people, not neutral tools; they want you to use them in particular ways and for long periods because that’s how they make their money. Companies like Google are driven into a “race to the bottom of the brain stem.” These apps were designed to put slot machines in our pockets, exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.

✦ 2. Digital Minimalism

Digital minimalists constantly perform implicit cost-benefit analyses. If a new technology offers little more than a minor diversion or trivial convenience, I believe we ignore it. Even when a new technology promises to support something we value, it must still pass a stricter test: Is this the best way to use technology to support this value? If the answer is no, I think we should optimize the tech or search out a better option.

By working backward from our deep values to our technology choices, I think we transform these innovations from a source of distraction into tools to support a life well-lived. By doing so, I believe we break the spell that has made so many people feel like they’re losing control to their screens. I don’t believe any potential benefit is enough to start using a technology. I think we should be wary of missing out on something that’s even slightly interesting or valuable. Indeed, when I first started writing publicly about the fact that I’ve never used Facebook, people in my professional circles were aghast for exactly this reason. “Why do I need to use Facebook?” I would ask. “I can’t tell you exactly,” they would respond, “but what if there’s something useful to you in there that you’re missing?”

I think we believe that the best digital life is formed by carefully curating tools to deliver massive and unambiguous benefits. I believe we tend to be incredibly wary of low-value activities that can clutter up our time and attention and end up hurting more than they help. I don’t mind missing out on small things; what worries me much more is diminishing the large things that I already know for sure make a good life good.

To make these abstract ideas more concrete, I’ve uncovered some real-world examples of digital minimalists in my research on this emerging philosophy. For some, the requirement that a new technology strongly supports deep values led to the rejection of services and tools that our culture commonly believes to be mandatory. Tyler, for example, originally joined the standard social media services for the standard reasons: to help his career, to keep him connected, and to provide entertainment. Once Tyler embraced digital minimalism, however, he realized that although he valued all three of these goals, his compulsive use of social networks offered at best minor benefits, and did not qualify as the best way to use technology for these purposes. So he quit all social media to pursue more direct and effective ways to help his career, connect with other people, and be entertained.

✦ 3. The Digital Declutter

To adopt digital minimalism, I don’t recommend gradual habit changes, as the engineered attraction and convenience will likely cause you to revert. Instead, I suggest a rapid transformation, executed with enough conviction to stick, which I call the digital declutter.

This process involves setting aside a 30-day period to break from optional technologies, exploring and rediscovering satisfying and meaningful activities, and then, at the end of the break, reintroducing technologies from a blank slate, determining each technology’s value and how to maximize it. Much like decluttering your house, this experiment resets your digital life, replacing distracting tools with intentional behaviors to support your values.

While the second part of this book offers strategies for a sustainable digital minimalist lifestyle, I suggest starting with the declutter, then optimizing your setup. Getting started is the most important step.

In early December 2017, I summarized this process in an email to my mailing list, seeking volunteers for a digital declutter in January. I expected 40-50 volunteers, but over 1,600 signed up. In February, I gathered detailed reports from participants about their technology rules during the declutter and their decisions when reintroducing technologies.

Two conclusions became clear after reviewing hundreds of dissections. First, the digital declutter works. People were surprised by how cluttered their digital lives had become with reflexive behaviors and compulsive tics. By stepping away from these technologies for thirty days, they were able to step back and better understand what they truly valued and what just held their attention. Many participants mentioned they rediscovered hobbies and interactions they forgot they loved.

The other conclusion I found clear was that a digital declutter is not easy. Many people gave up within the first few days, while others drastically reduced their ambitions mid-month, concluding it was more difficult than they anticipated. It’s important to understand these difficulties to effectively guide others through this process. With the experiment completed, I identified four basic strategies that separated participants who successfully completed the declutter from those who struggled, each strategy corresponds to one of the four common problems you might encounter when attempting the digital declutter yourself. By understanding these challenges and preparing these strategies, I believe anyone can successfully navigate the digital declutter process.

PART 2 Practices

✦ 4. Spend Time Alone

In an increasingly connected world, I think we are losing the ability to be alone with our own thoughts. I believe this loss has profound consequences, not only for our well-being, but also for our ability to navigate complex situations and generate creative ideas.

Solitude requires you to resist the urge to fix your attention on something external. You can think, observe, and interact, but all of these activities must be conducted solely within your own mind. I believe it’s inaccurate to think of time spent with other people as the opposite of solitude. If I’m at a crowded party but spend the evening lost in thought, oblivious to my surroundings, I’m technically among others, but still experiencing solitude. However, if I’m alone in my house but absorbed in a television show, I am not experiencing solitude but instead engaging in a pseudo-social interaction with the cast and writers of the show.

One of the reasons solitude is so important is that it is what allows you to clarify hard problems, I think. It provides an environment free from distraction in which you can patiently untangle the complex knots of modern life. The solitude deprivation many now experience is devastating to this capacity for good reason: sustained focused thought requires you to resist the flood of input that defines the modern information age.

Solitude can also improve your mood. I believe that solitude is not a luxury; it’s a necessity for processing and making sense of your experiences. Modernity has forced many people to give up on solitude, but it is not easy to give up on an essential human need without consequence. One of the reasons why digital minimalists are so calm and content is that they have rediscovered the importance of regularly spending time alone with their own thoughts.

I think many people avoid solitude not because they dislike it, but because they don’t know what to do with it. They’ve become so accustomed to having their attention guided by external stimuli that they’ve lost the ability to generate their own internal stimuli. This makes solitude an anxious and uncomfortable experience. I believe that solitude requires practice. You must be willing to spend time alone with your thoughts, even if it’s uncomfortable at first. Eventually, you will learn to enjoy it.

For those unfamiliar with extended reflection, I suggest starting small. Try spending just a few minutes each day alone with your thoughts. Gradually increase the amount of time you spend alone, until you can comfortably spend an hour or more in solitude. During this time, resist the urge to check your phone or engage in any other form of external stimulation. Simply allow yourself to think and observe. I think you’ll be surprised at how much you can learn about yourself and the world around you by simply spending time alone with your thoughts.

✦ 5. Don’t Click “Like”

Social media companies promote shallow connection because it benefits their bottom line, but this is not a natural feature of the technology. I believe there are better ways to leverage these tools that can actually strengthen your relationships. In this chapter, I’ll try to convince you to dramatically reduce your use of “liking” and commenting online and to embrace instead high-bandwidth conversation.

The logic here is simple. If you are serious about prioritizing real-world relationships, then you should deploy your limited time and attention in ways that maximize the amount of context and nuance conveyed during these interactions. I think clicking a heart icon below a photo or dashing off a quick comment in response to a friend’s post can’t compare to a phone call or getting together in person. A real conversation allows for tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, immediate reactions, and spontaneous tangents—all the crucial signals that allow two people to feel heard and understood.

In this chapter, I’ll argue that you’ll strengthen your relationships by reducing social media interactions and investing more in high-bandwidth communication. To begin this argument, I’ll share my perspective as someone who largely avoids social media but still maintains an active social life. From this viewpoint, I believe that the low-bandwidth interactions are more trouble than they’re worth, replacing richer interactions that would have occurred in their absence. I feel these interactions are a net negative for my relationships.

The core of my case against social media interaction is that I think it degrades conversation. A real conversation unfolds in real time and requires you to actually listen to what the other person is saying. Low-bandwidth online comments, by contrast, eliminate this crucial give-and-take. The rise of text-based online communication also eliminates many of the other social cues that make real-world interaction so rich.

These are not small details. Our species evolved for hundreds of thousands of years in small, intimate groups where subtle signals in tone and body language played a crucial role in creating cohesion. We are hardwired to crave the complete picture offered only by high-bandwidth communication, which is why relying too heavily on low-bandwidth interactions can leave us feeling strangely isolated—a sentiment I believe is at the heart of the distress surrounding modern digital life. High-quality conversation is the bedrock of human connection; if you want to fortify your relationships, I encourage you to treat such interactions as sacred. This is not something to degrade lightly.

✦ 6. Reclaim Leisure

The internet is not designed to provide you with satisfying leisure. It’s designed to keep you clicking as often as possible, for as long as possible. I believe this goal is in direct opposition to the type of high-quality, restorative experiences that the human brain requires to feel relaxed and content. I think we must take leisure seriously if we want to claim back our minds from the attention economy.

To make this case, I’ll begin with the idea of leisure itself, demonstrating how it can provide benefits far beyond simple relaxation. From there, I’ll move to a more detailed discussion of what I call high-quality leisure, which is active and requires effort. Finally, I’ll acknowledge the elephant in the room. Modern digital life is engineered to diminish our opportunities for high-quality leisure, replacing it with low-quality digital pastimes. I think we must push back against this trend by strategically cultivating demanding and engaging alternatives to screen-based distraction.

I’ve noticed that many equate leisure with relaxation, and assume that this is leisure’s main benefit. While relaxation is certainly part of leisure, I believe that it’s far from the whole story. Leisure activities pursued with intention can provide meaning to your life far beyond the immediate pleasure they deliver. I think it’s this deeper value that helps explain why high-quality leisure is so important to digital minimalists, and why they fight so hard to protect it from digital encroachment.

I think we should embrace activities that generate real value in the world, provide real meaning in your life, and foster real connection with people you care about. You might be exhausted at the end of it, but you go to bed feeling like you achieved something. High-quality leisure is not easy, and it’s the challenge that makes this type of leisure so fulfilling.

As a culture, I believe we’ve forgotten this distinction between demanding and passive leisure. Instead, we’ve fallen into a state of what I call leisure confusion, in which we believe that the goal of leisure is to do as little as possible, or to passively receive stimulation (like watching a video or scrolling through a feed). But this approach to leisure, while perhaps relaxing in the short-term, is not ultimately satisfying. The joy of tackling hard challenges is one of life’s most consistent sources of meaning, and in our leisure time, we should seek out opportunities to cultivate this feeling.

✦ 7. Join the Attention Resistance

I think it’s important to distinguish between technology that’s designed to support you and that which is designed to exploit you. I call those who are able to make that distinction, and then deploy technology accordingly, members of the attention resistance. I’ve found that these people thrive in our current age of digital overload.

To understand this claim, I’ll begin with the specific technologies they use to resist the pull of the attention economy, then provide a close examination of the broader strategies they deploy, and finally, I’ll touch on the unique challenges faced by members of the attention resistance, and how best to respond to them.

One of the most effective strategies for resisting digital distraction is to use technology to automate and optimize your digital habits. The idea here is simple: I think many of our worst digital habits come from the fact that we’re forced to make a lot of small decisions throughout the day about when and how to use different technologies. Each decision introduces a chance to succumb to distraction.

As a practical example, consider email. I think many professionals now struggle to keep their inboxes under control, and the constant checking for new messages throughout the day frays their focus and leads to an agitated state of mind. To push back against this dynamic, members of the attention resistance often adopt strict email policies that make it easier to control when they engage with their inbox.

Another common strategy among members of the attention resistance is to leverage high-tech tools in their effort to make their digital lives more intentional. The idea here is simple: I think many of our worst digital habits come from the fact that we’re forced to make a lot of small decisions throughout the day about when and how to use different technologies. Each decision introduces a chance to succumb to distraction. By automating the decision-making process and optimizing your digital habits, I believe we can reclaim our attention and focus on more important things. This allows them to extract real value from technology without losing control.

They aren’t avoiding technology, but using it in a way that protects them from exploitation, such as using website blockers or specialized apps that control when and how they can access certain sites or services. I’ve learned that these techniques offer a powerful way to reclaim control over one’s attention.

Finally, I think members of the attention resistance accept the responsibility of maintaining and defending their intentional digital lives, constantly adapting their approach to the ever-changing technological landscape. It’s not enough to adopt a few high-tech tools or strategies; it’s about embracing a mindset of constant vigilance. This ongoing commitment solidifies your resolve to live intentionally in an attention economy.

✦ Conclusion

As I conclude, I hope you recognize that digital minimalism isn’t about deprivation but intentionality. The goal isn’t to reject technology wholesale, but to thoughtfully curate its role in our lives, aligning it with our values and aspirations. I think it’s about reclaiming control, focusing on what truly matters, and cultivating a life rich in meaning and connection.

I understand this philosophy isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. The specifics of digital minimalism will vary depending on individual values, professions, and lifestyles. However, I’ve tried to provide a framework that can be adapted to suit different needs and preferences. The digital declutter offers a practical starting point for anyone seeking to reset their relationship with technology.

If you embrace these ideas, you can experience a transformative shift in your daily life. By prioritizing solitude, nurturing offline relationships, and engaging in high-quality leisure activities, you can discover a renewed sense of focus and purpose. The attention resistance offers strategies for navigating the digital landscape without succumbing to its manipulative tactics.

I think, ultimately, digital minimalism is about living deliberately in an age of distraction. It’s about making conscious choices about how we spend our time and energy, and ensuring that technology serves our best interests rather than the other way around. It’s about creating a life that is both meaningful and fulfilling, a life where technology enhances our experiences rather than diminishing them. It is my sincere hope that this book has inspired you to embark on your own journey toward digital minimalism, and to discover the profound benefits of a more focused and intentional life.

For People

– Professionals

– Parents

– Students

– Entrepreneurs

– Creatives

Learn to

– Focused Attention

– Intentional Technology Use

– Value-Driven Living

– Enhanced Satisfaction

– Rediscovering Leisure